“I must have mud and you must have adventure. Oh why,” wailed Ploppa, with a smothered sob, “cannot people who like each other like the same things?”

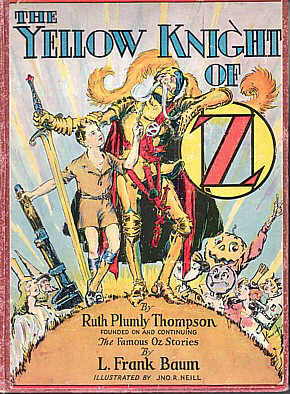

In The Yellow Knight of Oz, Ruth Plumly Thompson produced one of her most jumbled, yet most delightful, books, a mix of mud, Arthurian knights, irritated underground dwellers, trees melting into people, and science fiction. The result should not make any sense, and yet it does, creating an often moving tale of how, even in the best and most magical of fairylands, you may not always get the life you wished for.

The story begins in the Emerald City, where the gentle Sir Hokus is troubled. Not because, as you might be thinking, he has finally realized that no matter how many times her country is threatened or outright invaded, Ozma will never set up a security system or even the simplest of defense plans, but because he has never, in his entire and near endless life, completed a quest. He decides to go on one, despite not knowing what he might be questing for. The girls of the Emerald City are delighted at the thought—they regard it as sort of a picnic—and scoff at any suggestion that they should be working on embroidery instead:

“How stuffy!” sniffed Bettsy Bobbin, sliding carefully into his lap, which his armor made rather hard and uncomfortable. “How old-fashioned. Now don’t be quaint! What fun is it watching from a tower? And this embroidery and so on that you talk about ruins the eyes, and you know it!”

Despite this speech, Sir Hokus evades his friends, striking out across Oz on his own. Meanwhile, a young boy from Long Island, called Speedy, is heading to Oz—via rocket. Rocket!

If this seems like transportation overkill, I should note that the rocket was originally heading to Mars. Oz, Mars—it’s an understandable mistake. I draw attention to this minor plot point because a) in a long line of horrific storms, shipwrecks, whirlpools, strange balloons, chants and wishes, this is the first time, as far as I know, that anyone has taken a rocket to Oz, and b) this may be the ultimate coolest way to get to Oz, ever, and c) this was, hands down, my favorite scene from the Thompson books ever when I was a kid, not so much because of any literary qualities or humor or anything but just because, rockets! Oz! Geekdoms united at last. And even now I confess to a fondness for the idea of reaching worlds of pure fantasy by rocketship.

I think I need a moment. There.

It’s not at all clear how the rocket was expected to reach Mars, much less in the suggested day and a half. (My chief kid critique of the book, based entirely on Voyager photos, was that a rocket of the size in the illustrations would never make it to Mars in the first place, much less that quickly.) Thompson speeds past any physics and probability issues right into the real—well, ok, fantastic problems faced by the Subterraneans, who have just had Speedy’s rocket crash into them. They are not too happy about this, and Speedy barely manages to escape to the surface with part of the rocket and a lovely maiden named Marygolden. Marygolden is quite happy to have an adventure, and quite unaware of any gender problems that might hold her back—although Speedy thinks of a few.

(Incidentally, Speedy proudly announces his political affilation: Republican. Hmm.)

Soon enough the two of them meet up with Sir Hokus and the Comfortable Camel, in a lovely Arthurian setting complete with enchanted knights, towers, quests and a jester named Peter Pan apparently on leave from a Howard Pyle book. Or I should say, a mostly Arthurian setting. Several knights adamantly—and quite sensibly—refuse to be brave, in a scene that could easily squeeze into a Monty Python sketch. And Thompson does not quite give the expected ending here. For although Speedy saves two kingdoms, rescues a princess, taught her about the world and gained her friendship, and even learned to rethink his thoughts about girls, in the end, and against all expectations, he does not get the girl. Instead, Speedy watches Marygolden walk away with Sir Hokus, now transformed into the handsome young prince Corum—a transformation and marriage that will take the knight away from his expected, and delightful, life in the Emerald City. (If you ignore the nearly endless invasions, that is.)

I should note that not all of the later Royal Historians of Oz approved of this change: John R. Neill, Eloise Jarvis McGraw and Lauren McGraw all chose to ignore it. But in the context of this book, it works beautifully—not merely because the knight who began with disapproving of the very idea of girls having adventures ends up professing his love for a girl who likes them very much. But also because Marygolden’s marriage works within the book’s themes of friendship, desire, and shared interests. She and Speedy may like each other, but they do not like the same things. Speedy belongs with Long Island and rockets; Marygolden belongs with Arthurian knights. (See, the rocket makes a bit more sense now.) It echoes a scene earlier in the book, when Ploppa, a turtle with a decided lust for mud, mourns that he cannot join Sir Hokus, who does not have any lust for mud.

I don’t know that I entirely agree that love, much less friendship, cannot survive when people do not like the same things, but I will certainly agree with Ploppa that sometimes people who like each other will not like the same things. And I can agree with Thompson that life, even in a fairyland, is not always fair, and not all relationships will go the way people hope they might. I had not expected to find this much realism in a book with rockets and knights and melting trees, but Thompson once again finds the unexpected in Oz.

Ozma, however, still manages to fail in a book where she barely makes an appearance. (I’m beginning to think failure is one of her fairy gifts.) She fails to notice that her knight—one of the Emerald City’s only defenders—her Magic Picture, and a Comfortable Camel under her protection have all vanished. This, only a short time after her city has been invaded, so you would think she’d at least be trying to be on the alert. True, the Comfortable Camel reveals that Ozma has finally installed an electric alarm system, but it should surprise no one at this point—I have no fears of spoilers here—that the electric alarm system is, to put it kindly, completely useless. Much worse, at the end of the book, Ozma chooses to leave the slaves of Samandra in slavery.

In some justice to Ozma, my sense is that this last may be less of an Ozma fail, and more a reflection of Thompson’s own careless attitudes towards slavery, which I’ll be discussing in more depth later. Regardless, Ozma fails to end slavery in a kingdom she technically overrules.

Ozma does, I must admit, manage to recognize Prince Corum as the transformed Sir Hokus, and—don’t fall over in shock—for once, she actually does something useful. And this time, when she needs guidance on the whole how to punish people again, it comes across more as a queen wishing to consult the injured parties, and less as a queen at a loss for what to do. Which I would take as a positive sign for her future, but I’ve read ahead, and I must warn you all: no, no, it isn’t.

Mari Ness rather hopes that if she ever reaches Oz, she can have the life she wants. It involves endless books and eating all the things doctors generally don’t approve of. She lives in central Florida.